A senior scientist who has become the latest recruit of the Oxford Vaccine Group’s impressive roster of researchers, Professor Ferreira joined the University from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine where she made her name leading clinical trials for the Oxford COVID-19 vaccine, among other key pieces of research.

‘I was both leading a very large research programme as well as being the head of clinical sciences department in Liverpool. And I knew (Director of the Oxford Vaccine Group, Professor Sir) Andy Pollard from our field of work, which focused on human challenge models,’ she says, reflecting on a small part of a journey that took her from Brazil to Leicester, Liverpool and finally Oxford.

Professor Ferreira had been invited to sit on a data safety monitoring board for the phase one trials of the vaccine when a call for help came.

‘I remember the very early discussions where [Professor Pollard] mentioned, “Listen, we're going to now expand; we need many sites to do phases two and three of the vaccine”, and we were going to expand to…I think it was initially 10 or 14, then it became 18 sites,’ she recalls.

Stepping up to lead a COVID-19 trial

Professor Ferreira called Professor Pollard up and told him she could help.

‘I had a team of, at the time, about 40 people; real experts on vaccination, recruitment of participants and follow up. But we had stopped our programme because of the pandemic.’

They agreed to set up a site in Liverpool, and Professor Ferreira and her team put out a call for help from doctors and nurses. Around 60 answered, ramping up their numbers from 40 to 100.

‘It was a military operation. We took over two entire buildings – all three floors – to make sure that we could maintain the social distance. And we recruited and vaccinated almost 1,000 participants. It was really a mega operation. And this is like in weeks, right? I think it was two or three weeks,’ she says, emphasising that – understandably – it was a ‘stressful’ period in her life, especially as she had a young family at the time.

So, how did she cope?

‘So let's take a few steps back; how was I able to [lead a critically important clinical trial] with a two year old? First, having a very supportive husband. Without that, I would not even be able to think about leading a team to vaccinate 1,000 people, right? Because it was a very intense time,’ she says, laughing.

Yet, leading clinical trials some days from home at the time with a young child was no laughing matter. Professor Ferreira had no access to childcare in the first four weeks and was surviving on four hours of sleep a night. However, she gives full credit to her team for getting through this critical period.

‘The numbers (of COVID cases) were creeping up again, the results were not out, we did not have a vaccine. But the team was getting behind the trial and going, “We're almost there, we're going to get a vaccine and there is a big chance the vaccine is going to work.”

‘And we were not alone as well – there were all the other sites. We were having weekly calls, and everybody was on the same page,’ she says of the experience.

The thought of being apart from her family back home in Brazil also focused her mind.

‘A big part of why I was doing this was because I knew this vaccine was going to be accessible to everyone globally. I was doing this because I wanted to be able to hug my mother again, I was doing this because my father in Brazil might receive the vaccine that we were developing here. It was a similar motivation for everyone.’

Strong family support

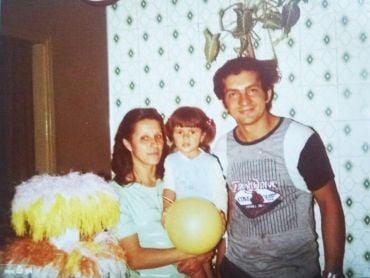

Family has been a key factor in Professor Ferreira’s growth as a scientific researcher. She grew up in Campinas, an hour away from Sao Paolo, with her parents and brother. Her father is a mechanic while her mother stayed at home to look after her children. Both parents, however, shaped her journey.

‘From my father, I think that’s where I got my work ethic from – like working hard, being honest, and just being a hard worker in general was really important to him,’ she describes.

‘My mother was a very calm and caring woman. She literally lived her life to take us to classes and take us around – the whole support that I needed. She learned how to drive just be able to take me to a better school, which was a little bit further from my house and not easily accessible by bus.

‘So my father bought her a very old small car, you know, a fairly small cheap car. And she was so petrified of driving, but she learnt just to be able to take us to that better school.’

Professor Ferreira developed an interest in science from a very young age, due in no small part to her teacher at the time who helped her engage with the subject. This interest eventually developed into a passion.

‘I loved insects and small crawly things,’ she says.

‘And I think that's also one of the reasons I decided to go into such biological sciences rather than study medicine because I really like biology as a wider area of expertise.’

Another key moment that helped solidify her path to becoming a scientific researcher was the successful cloning of a certain sheep named Dolly.

‘Every single news magazine (on Dolly), or whatever I could get my hands on, I was grabbing it,’ she remembers.

‘And then there was the Human Genome Project that was also published.

'And I remember, I even saved up some money to buy a nature journal which would have the full human genome. And so when I went to university, I knew that I wanted to work in these kind of fields such as biotechnology, genetic engineering, and all of that.’

And indeed Professor Ferreira did go to the University of Sao Paolo in 2001, gaining experience in a laboratory working with DNA vaccines for respiratory infections before jumping straight into her postgraduate learning. Her PhD focused on preclinical models testing vaccine immunology for respiratory infections, mainly from pneumococcal bacteria that causes pneumonia. Eventually, she received funding from the Brazilian government to study further at the University of Leicester for six months.

‘I arrived in January 2009, and it was really cold. And it was snowing,’ she describes.

‘There was a huge cultural difference, like the food and the language, and I remember very clearly that in the first month I could not sleep because I had so much English in my mind that I was dreaming in English,’ she adds, referring to her challenges in learning a new language.

From Brazil to the UK

She went back to Brazil and was offered a postdoctoral job shortly after at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, working under Professor Stephen Gordon who at the time was planning to develop a human challenge model involving pneumococcus. Under his mentorship, the scientist who would eventually lead clinical trials on a COVID-19 vaccine on Merseyside thrived.

‘About five years in, I remember the day that he came to me and said, “Listen, I'm going to go back to live in Malawi. What about you take over the team?”’ she says.

‘I was a postdoc at the time, I did not even have a lectureship yet and not a lot of management experience.’

She learned as she did the job whilst being left in charge of a team of five. She received executive coaching and management that helped during the rapid expansion of her team to 35 within a year. This expansion was supported by some timely grants, not least from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Back to business

After the disruption in their research caused by COVID-19, Professor Ferreira’s team is back to focusing on respiratory viruses such as RSV, influenza and pneumonia. In particular, they are running a very large clinical trial testing two licenced vaccines for pneumonia to see whether they protect against a particular type of pneumococcus that has been driving increasing numbers of pneumonia cases in the UK and the rest of the world. However, the pandemic also provided an opportunity for the team to combine their newfound focus on coronavirus with their normal research.

‘We actually recruited 400 patients with coronavirus in hospital and 100 healthcare workers to follow them up and look at a couple of things. Mucosal immune response and the interplay between SARS-CoV2 and pneumococcus bacteria in the nose,’ she recalls.

‘So, looking at responses to coronavirus and the interaction between the bacteria and coronavirus; we published a couple of very good papers from that work. We did not completely stop our research (during the pandemic) but it was incredible that this was running in parallel with the main vaccine studies.’

Once-in-a-lifetime opportunity

It was not so long after COVID-19 restrictions started easing that Professor Ferreira then got the call from the University of Oxford.

‘I had a working relationship with Andy for many years. And because, he knew about my work and I knew about his work, he approached me and asked if I would like to come to join the Oxford Vaccine Group,’. He had approached me about 5 years ago, but it was not the right time for me,’ she says.

‘And this is the craziest thing. I was not looking to move. I had a team of 46 people in Liverpool, I was the head of department. I had amazing clinical facilities and space. And I had been there for 13 years.

‘But when Andy mentioned [the job], instantly I said this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. For me as a scientist, I really had a great experience working with the Oxford Vaccine Group. And I think that was also part of my decision.’

Despite being about to embark on some major refurbishments at her Liverpool home, Professor Ferreira packed up her bags and moved south with her supportive family. She still spends a fifth of her time in Liverpool as part of what she calls a ‘golden marriage’ between LSTM and Oxford – it is hoped that there will be high-profile research collaborations between the two institutions in the near future.

When asked if there were any moments where the impact of her critically important work during the pandemic really hit home, Professor Ferreira does not hesitate in her response.

‘I remember I was in Brazil when my father got a (COVID-19) vaccine and I drove him to take the vaccine – it was the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine,’ she recalls.

‘My father was in tears, we were all in tears. It was a really, really amazing moment where he went back home and understood that what I was doing could have an impact on the entire world, it was part of a bigger thing.’

And certainly, due to her ongoing work on respiratory diseases using human challenge models at Oxford, Professor Daniela Ferreira will continue to have a global impact in vaccine research.